This file is a deprecated introduction to the corpkit Python API. It still exists because it contains a lot of useful information and advanced examples that are not found elsewhere. It is deprecated because better documentation is available at ReadTheDocs.

- What's in here?

- Installation

- Quickstart

- More detailed examples

- Working with coreferences

- Building corpora

- Concordancing

- Systemic functional stuff

- Keywording

- Parallel processing

- More complex queries and plots

- Contact

- Cite

Essentially, the module contains classes, methods and functions for building and interrogating corpora, then manipulating or visualising the results.

First, there's a Corpus() class, which models a corpus of CoreNLP XML, lists of tokens, or plaintext files, creating subclasses for subcorpora and corpus files.

To use it, simple feed it a path to a directory containing .txt files, or subfolders containing .txt files.

>>> from corpkit import Corpus

>>> unparsed = Corpus('path/to/data')With the Corpus() class, the following attributes are available:

| Attribute | Purpose |

|---|---|

corpus.subcorpora |

list of subcorpus objects with indexing/slicing methods |

corpus.features |

Corpus features (characters, clauses, words, tokens, process types, passives, etc.) |

corpus.postags |

Distribution of parts of speech |

corpus.wordclasses |

Distribution of word classes |

as well as the following methods:

| Method | Purpose |

|---|---|

corpus.parse() |

Create a parsed version of a plaintext corpus |

corpus.tokenise() |

Create a tokenised version of a plaintext corpus |

corpus.interrogate() |

Interrogate the corpus for lexicogrammatical features |

corpus.concordance() |

Concordance via lexis and/or grammar |

Once you've defined a Corpus, you can move around it very easily:

### corpus containing annual subcorpora of NYT articles

>>> corpus = Corpus('data/NYT-parsed')

>>> list(corpus.subcorpora)[:3]

### [<corpkit.corpus.Subcorpus instance: 1987>,

### <corpkit.corpus.Subcorpus instance: 1988>,

### <corpkit.corpus.Subcorpus instance: 1989>]

>>> corpus.subcorpora[0].path, corpus.subcorpora[0].datatype

### ('/Users/daniel/Work/risk/data/NYT-parsed/1987', 'parse')

>>> corpus.subcorpora.c1989.files[10:13]

### [<corpkit.corpus.File instance: NYT-1989-01-01-10-1.txt.xml>,

### <corpkit.corpus.File instance: NYT-1989-01-01-10-2.txt.xml>,

### <corpkit.corpus.File instance: NYT-1989-01-01-11-1.txt.xml>]Most attributes, and the .interrogate() and .concordance() methods, can also be called on Subcorpus and File objects. File objects also have a .read() method.

- Use Tregex, regular expressions or wordlists to search parse trees, dependencies, token lists or plain text for complex lexicogrammatical phenomena

- Search for, exclude and show word, lemma, POS tag, semantic role, governor, dependent, index (etc) of a token

- N-gramming

- Two-way UK-US spelling conversion

- Output Pandas DataFrames that can be easily edited and visualised

- Use parallel processing to search for a number of patterns, or search for the same pattern in multiple corpora

- Restrict searches to particular speakers in a corpus

- Works on collections of corpora, corpora, subcorpora, single files, or slices thereof

- Quickly save to and load from disk with

save()andload()

- Equivalent to

interrogate(), but return DataFrame of concordance lines - Return any combination and order of words, lemmas, indices, functions, or POS tags

- Editable and saveable

- Output to LaTeX, CSV or string with

format()

The code below demonstrates the complex kinds of queries that can be handled by the interrogate() and concordance() methods:

### import * mostly so that we can access global variables like G, P, V

### otherwise, use 'w' instead of W, 'p' instead of P, etc.

>>> from corpkit import *

### select parsed corpus

>>> corpus = Corpus('data/postcounts-parsed')

### import process type lists and closed class wordlists

>>> from corpkit.dictionaries import *

### match tokens with governor that is in relational process wordlist,

### and whose function is `nsubj(pass)` or `csubj(pass)`:

>>> criteria = {GL: processes.relational.lemmata, F: r'^.subj'}

### exclude tokens whose part-of-speech is verbal,

### or whose word is in a list of pronouns

>>> exc = {P: r'^V', W: wordlists.pronouns}

# interrogate, returning slash-delimited function/lemma

>>> data = corpus.interrogate(criteria, exclude=exc, show=[F,L])

>>> lines = corpus.concordance(criteria, exclude=exc, show=[F,L])

### show results

>>> print data, lines.format(n=10, window=40, columns=[L,M,R])Output sample:

nsubj/thing nsubj/person nsubj/problem nsubj/way nsubj/son

01 296 168 134 69 73

02 233 147 88 70 70

03 250 160 95 80 67

04 247 205 88 93 71

05 275 193 68 75 61

0 nk nsubj/it cop/be ccomp/sad advmod/when nsubj/person aux/do neg/not advcl/look ./at prep_at/w

1 /my dobj/Fluoxetine advmod/now mark/that nsubj/spring ccomp/be advmod/here ./, ./but nsubj/I a

2 y mark/because expl/there advcl/be det/a nsubj/woman ./across det/the prep_across/hall ./from

3 num/114 ccomp/pound ./, mark/so det/any nsubj/med nsubj/I rcmod/take aux/can advcl/have de

4 nsubj/Kat ./, root/be nsubj/you dep/taper ./off ./

5 /to xcomp/explain prep_from/what det/the nsubj/mark ./on poss/my prep_on/arm ./, conj_and/ne

6 det/the amod/first ./and conj_and/third nsubj/hospital nsubj/I rcmod/be advmod/at root/have num

7 e dobj/tv mark/while det/the amod/second nsubj/hospital nsubj/I cop/be rcmod/IP prep/at pcomp/in

8 nsubj/Ben ./, mark/if nsubj/you cop/be advcl/unhap

9 h ./of prep_of/sleep advmod/when det/the nsubj/reality advcl/be ./, nsubj/everyone ccomp/need n

The corpus.interrogate() method returns an Interrogation object. These have attributes:

| Attribute | Contains |

|---|---|

interrogation.results |

Pandas DataFrame of counts in each subcorpus |

interrogation.totals |

Pandas Series of totals for each subcorpus/result |

interrogation.query |

a dict of values used to generate the interrogation |

and methods:

| Method | Purpose |

|---|---|

interrogation.edit() |

Get relative frequencies, merge/remove results/subcorpora, calculate keywords, sort using linear regression, etc. |

interrogation.visualise() |

visualise results via matplotlib |

interrogation.save() |

Save data as pickle |

interrogation.quickview() |

Show top results and their absolute/relative frequency |

These methods have been monkey-patched to Pandas' DataFrame and Series objects, as well, so any slice of a result can be edited or plotted easily.

- Remove, keep or merge interrogation results or subcorpora using indices, words or regular expressions (see below)

- Sort results by name or total frequency

- Use linear regression to figure out the trajectories of results, and sort by the most increasing, decreasing or static values

- Show the p-value for linear regression slopes, or exclude results above p

- Work with absolute frequency, or determine ratios/percentage of another list:

- determine the total number of verbs, or total number of verbs that are be

- determine the percentage of verbs that are be

- determine the percentage of be verbs that are was

- determine the ratio of was/were ...

- etc.

- Plot more advanced kinds of relative frequency: for example, find all proper nouns that are subjects of clauses, and plot each word as a percentage of all instances of that word in the corpus (see below)

- Plot using Matplotlib

- Plot anything you like: words, tags, counts for grammatical features ...

- Create line charts, bar charts, pie charts, etc. with the

kindargument - Use

subplots=Trueto produce individual charts for each result - Customisable figure titles, axes labels, legends, image size, colormaps, etc.

- Use

TeXif you have it - Use log scales if you really want

- Use a number of chart styles, such as

ggplot,fivethirtyeightorseaborn-talk(if you've gotseaborninstalled) - Save images to file, as

.pdfor.png - Experimental interactive plots (hover-over text, interactive legends) using mpld3

There are quite a few helper functions for making regular expressions, making new projects, and so on, with more documentation forthcoming. Also included are some lists of words and dependency roles, which can be used to match functional linguistic categories. These are explained in more detail here.

You can get corpkit running by downloading or cloning this repository, or via pip.

Hit 'Download ZIP' and unzip the file. Then cd into the newly created directory and install:

cd corpkit-master

# might need sudo:

python setup.py installClone the repo, cd into it and run the setup:

git clone https://github.com/interrogator/corpkit.git

cd corpkit

# might need sudo:

python setup.py install# might need sudo:

pip install corpkit

# or, for a local install:

# pip install --user corpkitcorpkit should install all the necessary dependencies, including pandas, NLTK, matplotlib, etc, as well as some NLTK data files.

Once you've got corpkit, and a folder containing text files, you're ready to go:

### import everything

>>> from corpkit import *

### Make corpus object from path to subcorpora/text files

>>> unparsed = Corpus('data/nyt/years')

### parse it, return the new parsed corpus object

>>> corpus = unparsed.parse()

### search corpus for modal auxiliaries and plot the top results

>>> corpus.interroplot('MD')Output:

interroplot() is just a demo method that does three things in order:

- uses

interrogate()to search corpus for a (Regex- or Tregex-based) query - uses

edit()to calculate the relative frequencies of each result - uses

visualise()to show the top seven results

Here's an example of the three methods at work:

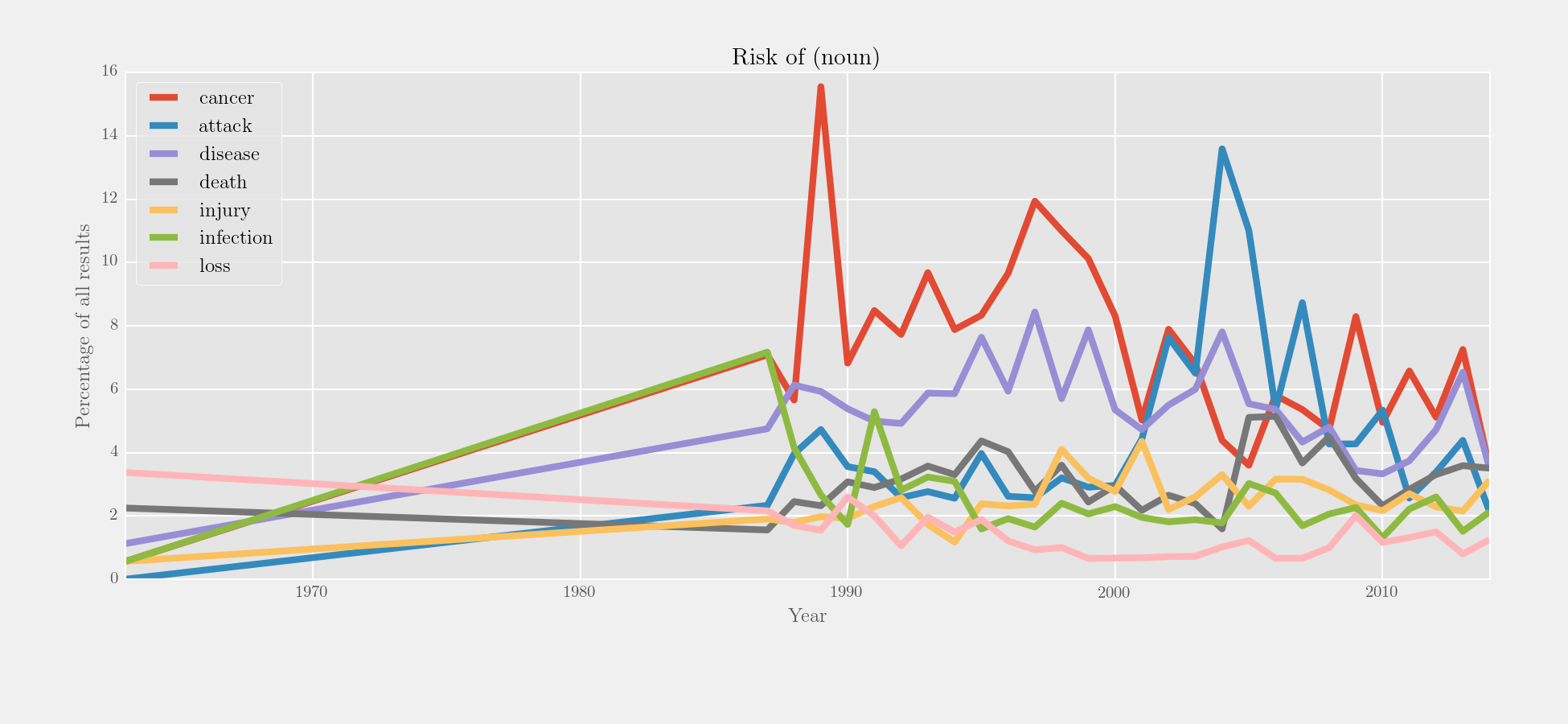

### make tregex query: head of NP in PP containing 'of' in NP headed by risk word:

>>> q = r'/NN.?/ >># (NP > (PP <<# /(?i)of/ > (NP <<# (/NN.?/ < /(?i).?\brisk.?/))))'

### search trees, exclude 'risk of rain', output lemma

>>> risk_of = corpus.interrogate({T: q}, exclude={W: '^rain$'}, show=L)

### alternative syntax which may be easier when there's only a single search criterion:

# >>> risk_of = corpus.interrogate(T, q, exclude={W: '^rain$'}, show=L)

### use edit() to turn absolute into relative frequencies

>>> to_plot = risk_of.edit('%', risk_of.totals)

### plot the results

>>> to_plot.visualise('Risk of (noun)', y_label='Percentage of all results',

... style='fivethirtyeight')Output:

In the example above, parse trees are searched, a particular match is excluded, and lemmata are shown. These three arguments (search, exclude and show) are the core of the interrogate() and concordance() methods.

the search and exclude arguments need a dict, with the thing to be searched as keys and the search pattern as values. Here is a list of available keys for plaintext, tokenised and parsed corpora:

| Key | Gloss |

|---|---|

W |

Word |

L |

Lemma |

I |

Index of token in sentence |

N |

N-gram |

For parsed corpora, there are many other possible keys:

| Key | Gloss |

|---|---|

P |

Part of speech tag |

X |

Word class |

G |

Governor word |

GL |

Governor lemma form |

GP |

Governor POS |

GF |

Governor function |

D |

Dependent word |

DL |

Dependent lemma form |

DP |

Dependent POS |

DF |

Dependent function |

F |

Dependency function |

R |

Distance from 'root' |

T |

Tree |

S |

Predefined general stats |

Allowable combinations are subject to common sense. If you're searching trees, you can't also search governors or dependents. If you're searching an unparsed corpus, you can't search for information provided by the parser. Here are some example search/exclude values:

| search/exclude | Gloss |

|---|---|

{W: r'^p'} |

Tokens starting with P |

{L: r'any'} |

Any lemma (often equivalent to r'.*') |

{G: r'ing$'} |

Tokens with governor word ending in 'ing' |

{F: funclist} |

Tokens whose dependency function matches a str in funclist |

{D: r'^br', GL: r'$have$'} |

Tokens with dependent starting with 'br' and 'have' as governor lemma |

{I: '0', F: '^nsubj$'} |

Sentence initial tokens with role of nsubj |

{T: r'NP !<<# /NN.?'} |

NPs with non-nominal heads |

If you'd prefer, you can make a dict to handle dependent and governor information, instead of using things like GL or DF. The following searches produce the same output:

>>> crit = {W: r'^friend$',

... D: {F: 'amod',

... W: 'great'}}

>>> crit = {W: r'^friend$', DF: 'amod', D: 'great'}By default, all search criteria must match, but any exclude criterion is enough to exclude a match. This beahviour can be changed with the searchmode and excludemode arguments:

### get words that end in 'ing' OR are nominal:

>>> out = corpus.interrogate({W: 'ing$', P: r'^N'}, searchmode='any')

### get any word, but exclude words that end in 'ing' AND are nominal:

>>> out = corpus.interrogate({W: 'any'}, exclude={W: 'ing$', P: N}, excludemode='all')The show argument wants a list of keys you'd like to return for each result. The order will be respected. If you only want one thing, a str is OK. One additional possibility is C, which returns the number of occurrences only.

show |

return |

|---|---|

W |

'champions' |

[W] |

'champions' |

L |

'champion' |

P |

'NNS' |

X |

'Noun' |

T |

'(np (jj prevailing) (nns champions))' (depending on Tregex query) |

[P, W] |

'NNS/champions' |

[W, P] |

'champions/NNS' |

[I, L, R] |

'2/champion/1' |

[L, D, F] |

'champion/prevailing/nsubj' |

[G, GL, I] |

'are/be/2' |

[GL, GF, GP] |

'be/root/vb' |

[L, L] |

'champion/champion' |

[C] |

24 |

Again, common sense dictates what is possible. When searching trees, only trees, words, lemmata, POS and counts can be returned. If showing trees, you can't show anything else. If you use C, you can't use anything else.

One major challenge in corpus linguistics is the fact that pronouns stand in for other words. Parsing provides coreference resolution, which maps pronouns to the things they denote. You can enable this kind of parsing by specifying the dcoref annotator:

>>> ops = 'tokenize,ssplit,pos,lemma,parse,ner,dcoref'

>>> parsed = corpus.interrogate(operations=ops)If you have done this, you can use coref=True while interrogating to allow coreferents to be mapped together:

>>> corpus.interrogate(query, coref=True)So, if you wanted to find all the processes a certain entity is engaged in, you can get a more complete result with:

>>> from corpkit.dictionaries import roles

>>> corpus.interrogate({W: 'clinton', GF: roles.process}, coref=True)This will count support in Clinton supported the independence of Kosovo, and also potentially authorize in He authorized the use of force. You can also toggle the representative=True and non_representative=True arguments if you want to distinguish between copula and non-copula coreference.

>>> corpus.interrogate({W: 'clinton', GF: roles.process}, coref=True, representative=False)corpkit's Corpus() class contains parse() and tokenise(), methods for created parsed and/or tokenised corpora. The main thing you need is a folder, containing either text files, or subfolders that contain text files. Stanford CoreNLP is required to parse corpora. If you don't have it, corpkit can download and install it for you. If you're tokenising, you'll need to make sure you have NLTK's tokeniser data. You can then run:

>>> unparsed = Corpus('path/to/unparsed/files')

### to parse, you can set a path to corenlp

>>> corpus = unparsed.parse(corenlppath='Downloads/corenlp')

### to tokenise, point to nltk:

# >>> corpus = unparsed.tokenise(nltk_data_path='Downloads/nltk_data')which creates the parsed/tokenised corpora, and returns Corpus() objects representing them. When parsing, you can also optionally pass in a string of annotators, as per the CoreNLP documentation:

>>> ans = 'tokenize,ssplit,pos'

### you can also set memory and turn off copula head parsing,

### or multiprocess the parsing job (though you'll want a big machine)

>>> corpus = unparsed.parse(operations=ans, memory_mb=3000,

... copula_head=False, multiprocess=4)Something novel about corpkit is that it can work with corpora containing speaker IDs (scripts, transcripts, logs, etc.), like this:

JOHN: Why did they change the signs above all the bins?

SPEAKER23: I know why. But I'm not telling.

If you use:

>>> corpus = unparsed.parse(speaker_segmentation=True)This will:

- Detect any IDs in any file

- Create a duplicate version of the corpus with IDs removed

- Parse this 'cleaned' corpus

- Add an XML tag to each sentence with the name of the speaker

- Return the parsed corpus as a

Corpus()object

When interrogating or concordancing, you can then pass in a keyword argument to restrict searches to one or more speakers:

>>> s = ['BRISCOE', 'LOGAN']

>>> npheads = interrogate(T, r'/NN.?/ >># NP', just_speakers=s)This makes it possible to not only investigate individual speakers, but to form an understanding of the overall tenor/tone of the text as well: Who does most of the talking? Who is asking the questions? Who issues commands?

When your data is parsed, Corpus objects draw on CoreNLP XML to keep everything seamlessly connected:

>>> corp = Corpus('data/CHT-parsed')

>>> corp.subcorpora['2013'].files[1].document.sentences[4235].parse_string

### '(ROOT (FRAG (CC And) (NP (NP (RB not) (RB just)) (NP (NP (NNP Metrione) ... '

>>> corp.subcorpora['1997'].files[0].document.sentences[3509].tokens[30].word

### 'linguistics'Once you have a parsed Corpus() object, enter corpus.features to interrogate the corpus for some basic frequencies:

>>> corpus = Corpus('data/sessions-parsed')

>>> corpus.featuresOutput:

Characters Tokens Words Closed class words Open class words Clauses Sentences Unmodalised declarative Mental processes Relational processes Interrogative Passives Verbal processes Modalised declarative Open interrogative Imperative Closed interrogative

01 26873 8513 7308 4809 3704 2212 577 280 156 98 76 35 39 26 8 2 3

02 25844 7933 6920 4313 3620 2270 266 130 195 109 29 19 35 11 5 1 3

03 18376 5683 4877 3067 2616 1640 330 174 132 68 30 40 29 8 12 6 1

04 20066 6354 5366 3587 2767 1775 319 174 176 83 33 30 20 9 9 4 1

05 23461 7627 6217 4400 3227 1978 479 245 154 93 45 51 28 20 5 3 1

06 19164 6777 5200 4151 2626 1684 298 111 165 83 43 56 14 10 6 6 2

07 22349 7039 5951 4012 3027 1947 343 183 195 82 29 30 38 12 5 5 0

08 26494 8760 7124 4960 3800 2379 545 263 170 87 66 36 32 10 6 5 4

09 23073 7747 6193 4524 3223 2056 310 149 164 88 21 26 22 10 5 3 0

10 20648 6789 5608 3817 2972 1795 437 265 139 101 34 34 39 18 5 3 2

11 25366 8533 6899 4925 3608 2207 457 230 203 116 39 48 47 15 10 4 0

12 16976 5742 4624 3274 2468 1567 258 135 183 72 23 43 22 4 3 1 6

13 25807 8546 6966 4768 3778 2345 477 257 200 124 45 50 36 15 12 3 2

Features such as relational/mental/verbal processes are difficult to locate automatically, so these counts are perhaps best seen as approximations. Even so, this data can be very helpful when using edit() to generate relative frequencies, for example.

Unlike most concordancers, which are based on plaintext corpora, corpkit can concordance grammatically, using the same kind of search, exclude and show values as interrogate().

>>> subcorpus = corpus.subcorpora.c2005

### C is added above to make a valid variable name from an int

### can also be accessed as corpus.subcorpora['2005']

### or corpus.subcorpora[index]

>>> query = r'/JJ.?/ > (NP <<# (/NN.?/ < /\brisk/))'

### T option for tree searching

>>> lines = subcorpus.concordance(T, query, window=50, n=10, random=True)Output (a Pandas DataFrame):

0 hedge funds or high-risk stocks obviously poses a greater risk to the pension program than a portfolio of

1 contaminated water pose serious health and environmental risks

2 a cash break-even pace '' was intended to minimize financial risk to the parent company

3 Other major risks identified within days of the attack

4 One seeks out stocks ; the other monitors risks

5 men and women in Colorado Springs who were at high risk for H.I.V. infection , because of

6 by the marketing consultant Seth Godin , to taking calculated risks , in the opinion of two longtime business

7 to happen '' in premises '' where there was a high risk of fire

8 As this was match points , some of them took a slight risk at the second trick by finessing the heart

9 said that the agency 's continuing review of how Guidant treated patient risks posed by devices like the

You can also concordance via dependencies:

### match words starting with 'st' filling function of nsubj

>>> criteria = {W: r'^st', F: r'nsubj$'}

### show function, pos and lemma (in that order)

>>> lines = subcorpus.concordance(criteria, show =[F,P,L])

>>> lines.format(window=30, n=10, columns=[L,M,R])Output:

0 ime ./:/; cc/CC/and det/DT/the nsubj/NN/stock conj:and/VBZ/be advmod/RB/hist

1 vmod/RB/even compound/NN/sleep nsubj/NNS/study ./,/, appos/NNS/evaluation cas

2 od:poss/NNS/veteran case/POS/' nsubj/NN/study ccomp/VBZ/suggest mark/IN/that

3 det/DT/a nsubj/NN/study case/IN/in nmod:poss/NN/today

4 cc/CC/but det/DT/the nsubj/NN/study root/VBD/find mark/IN/that cas

5 pound/NN/a amod/JJ/preliminary nsubj/NN/study case/IN/of nmod:of/NNS/woman c

6 case/IN/for nmod:for/WDT/which nsubj/NNS/statistics acl:relcl/VBD/be xcomp/JJ/avai

7 amod/JJR/earlier nsubj/NNS/study aux/VBD/have root/VBN/show mar

8 ay det/DT/the amod/JJR/earlier nsubj/NNS/study aux/VBD/do neg/RB/not ccomp/VB

9 /there root/VBP/be det/DT/some nsubj/NNS/strategy ./:/- dep/JJS/most case/IN/of

You can search tokenised corpora or plaintext corpora for regular expressions or lists of words to match. The two queries below will return identical results:

>>> r_query = r'^fr?iends?$'

>>> l_query = ['friend', 'friends', 'fiend', 'fiends']

>>> lines = subcorpus.concordance({W: r_query})

>>> lines = subcorpus.concordance({W: l_query})If you really wanted, you can then go on to use concordance() output as a dictionary, or extract keywords and ngrams from it, or keep or remove certain results with edit(). If you want to give the GUI a try, you can colour-code and create thematic categories for concordance lines as well.

Because I mostly use systemic functional grammar, there is also a simple tool for distinguishing between process types (relational, mental, verbal) when interrogating a corpus. If you add words to the lists in dictionaries/process_types.py, corpkit will get their inflections automatically.

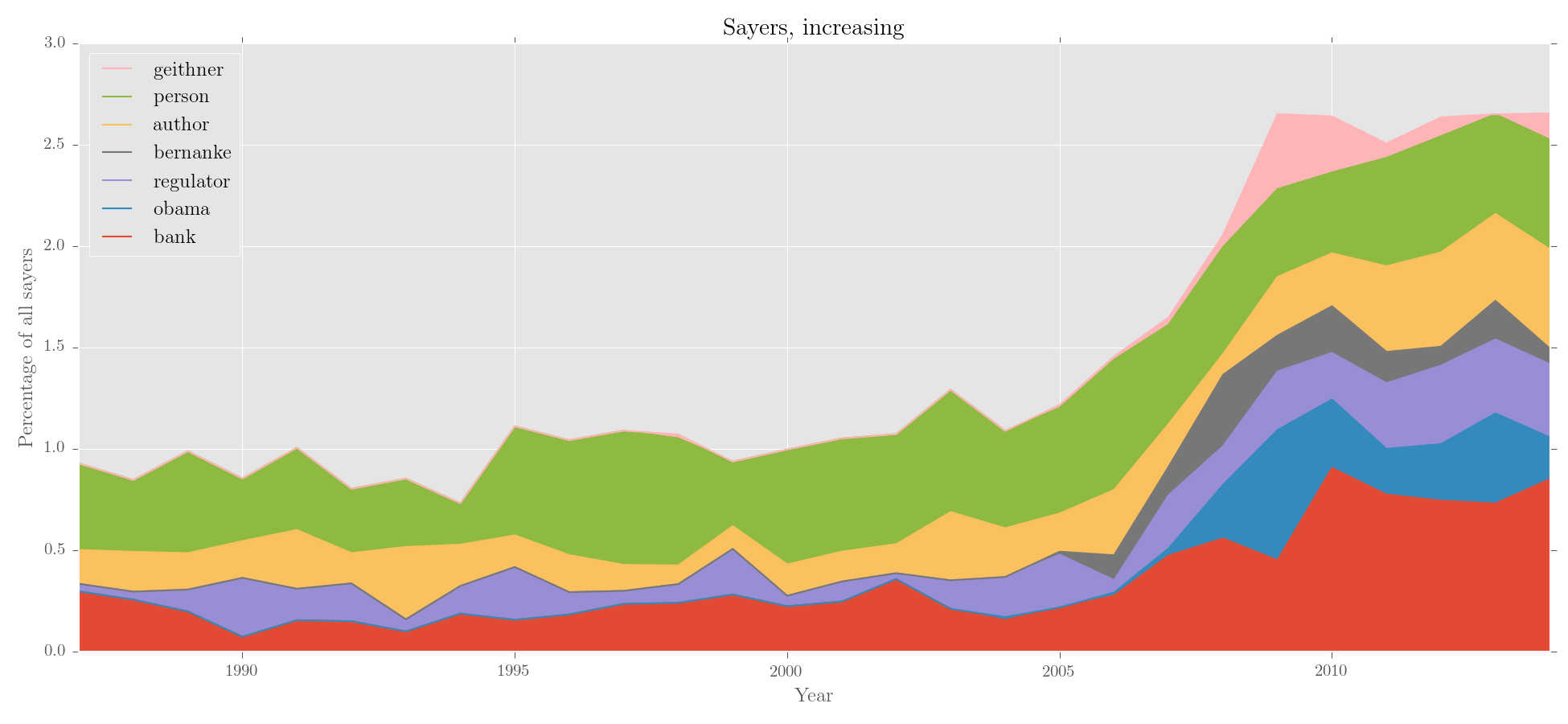

>>> from corpkit.dictionaries import processes

### match nsubj with verbal process as governor

>>> crit = {F: '^nsubj$', G: processes.verbal}

### return lemma of the nsubj

>>> sayers = corpus.interrogate(crit, show=L)

### have a look at the top results

>>> sayers.quickview(n=20)Output:

0: he (n=24530)

1: she (n=5558)

2: they (n=5510)

3: official (n=4348)

4: it (n=3752)

5: who (n=2940)

6: that (n=2665)

7: i (n=2062)

8: expert (n=2057)

9: analyst (n=1369)

10: we (n=1214)

11: report (n=1103)

12: company (n=1070)

13: which (n=1043)

14: you (n=987)

15: researcher (n=987)

16: study (n=901)

17: critic (n=826)

18: person (n=802)

19: agency (n=798)

20: doctor (n=770)

First, let's try removing the pronouns using edit(). The quickest way is to use the editable wordlists stored in dictionaries/wordlists:

>>> from corpkit.dictionaries import wordlists

>>> prps = wordlists.pronouns

# alternative approaches:

# >>> prps = [0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 13, 14, 24]

# >>> prps = ['he', 'she', 'you']

# >>> prps = as_regex(wl.pronouns, boundaries='line')

# or, by re-interrogating:

# >>> sayers = corpus.interrogate(crit, show=L, exclude={W: wordlists.pronouns})

### give edit() indices, words, wordlists or regexes to keep remove or merge

>>> sayers_no_prp = sayers.edit(skip_entries=prps, skip_subcorpora=[1963])

>>> sayers_no_prp.quickview(n=10)Output:

0: official (n=4342)

1: expert (n=2055)

2: analyst (n=1369)

3: report (n=1098)

4: company (n=1066)

5: researcher (n=987)

6: study (n=900)

7: critic (n=825)

8: person (n=801)

9: agency (n=796)

Great. Now, let's sort the entries by trajectory, and then plot:

### sort with edit()

### use scipy.linregress to sort by 'increase', 'decrease', 'static', 'turbulent' or P

### other sort_by options: 'name', 'total', 'infreq'

>>> sayers_no_prp = sayers_no_prp.edit('%', sayers.totals, sort_by='increase')

### make an area chart with custom y label

>>> sayers_no_prp.visualise('Sayers, increasing', kind='area',

... y_label='Percentage of all sayers')Output:

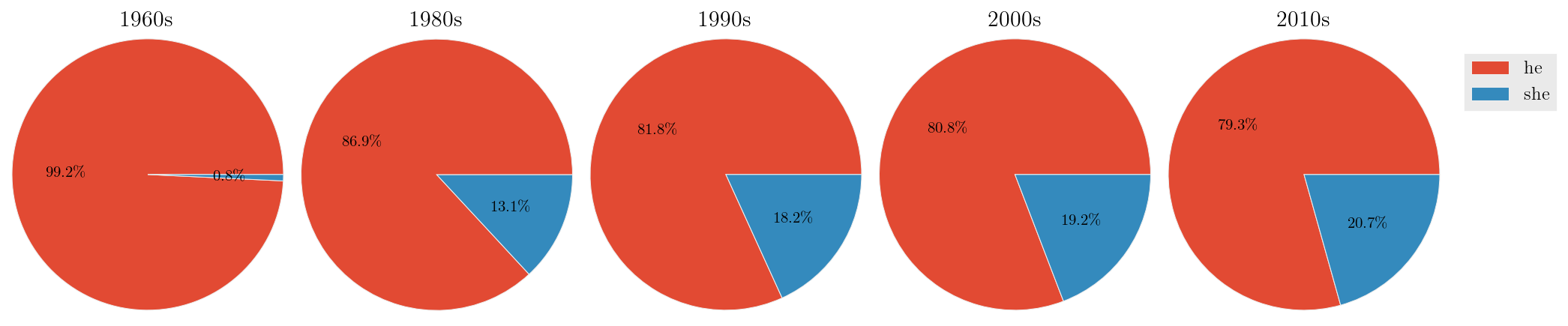

We can also merge subcorpora. Let's look for changes in gendered pronouns:

>>> merges = {'1960s': r'^196',

... '1980s': r'^198',

... '1990s': r'^199',

... '2000s': r'^200',

... '2010s': r'^201'}

>>> sayers = sayers.edit(merge_subcorpora=merges)

### now, get relative frequencies for he and she

### SELF calculates percentage after merging/removing etc has been performed,

### so that he and she will sum to 100%. Pass in `sayers.totals` to calculate

### he/she as percentage of all sayers

>>> genders = sayers.edit('%', SELF, just_entries=['he','she'])

### and plot it as a series of pie charts, showing totals on the slices:

>>> genders.visualise('Pronominal sayers in the NYT', kind='pie',

... subplots=True, figsize=(15,2.75), show_totals='plot')Output:

Woohoo, a decreasing gender divide!

As I see it, there are two main problems with keywording, as typically performed in corpus linguistics. First is the reliance on 'balanced'/'general' reference corpora, which are obviously a fiction. Second is the idea of stopwords. Essentially, when most people calculate keywords, they use stopword lists to automatically filter out words that they think will not be of interest to them. These words are generally closed class words, like determiners, prepositions, or pronouns. This is not a good way to go about things: the relative frequencies of I, you and one can tell us a lot about the kinds of language in a corpus. More seriously, stopwords mean adding subjective judgements about what is interesting language into a process that is useful precisely because it is not subjective or biased.

So, what to do? Well, first, don't use 'general reference corpora' unless you really really have to. With corpkit, you can use your entire corpus as the reference corpus, and look for keywords in subcorpora. Second, rather than using lists of stopwords, simply do not send all words in the corpus to the keyworder for calculation. Instead, try looking for key predicators (rightmost verbs in the VP), or key participants (heads of arguments of these VPs):

### just heads of participants' lemma form (no pronouns, though!)

>>> part = r'/(NN|JJ).?/ >># (/(NP|ADJP)/ $ VP | > VP)'

>>> p = corpus.interrogate(T, part, show=L)When using edit() to calculate keywords, there are a few default parameters that can be easily changed:

| Keyword argument | Function | Default setting | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

threshold |

Remove words occurring fewer than n times in reference corpus |

False |

'high/medium/low'/ True/False / int |

calc_all |

Calculate keyness for words in both reference and target corpus, rather than just target corpus | True |

True/False |

selfdrop |

Attempt to remove target data from reference data when calculating keyness | True |

True/False |

Let's have a look at how these options change the output:

### SELF as reference corpus uses p.results

>>> options = {'selfdrop': False,

... 'calc_all': False,

... 'threshold': False}

>>> for k, v in options.items():

... key = p.edit('keywords', SELF, k=v)

... print key.results.ix['2011'].order(ascending=False)Output:

| #1: default | #2: no selfdrop |

#3: no calc_all |

#4: no threshold |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| risk | 1941.47 | risk | 1909.79 | risk | 1941.47 | bank | 668.19 |

| bank | 1365.70 | bank | 1247.51 | bank | 1365.70 | crisis | 242.05 |

| crisis | 431.36 | crisis | 388.01 | crisis | 431.36 | obama | 172.41 |

| investor | 410.06 | investor | 387.08 | investor | 410.06 | demiraj | 161.90 |

| rule | 316.77 | rule | 293.33 | rule | 316.77 | regulator | 144.91 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ||||

| clinton | -37.80 | tactic | -35.09 | hussein | -25.42 | clinton | -87.33 |

| vioxx | -38.00 | vioxx | -35.29 | clinton | -37.80 | today | -89.49 |

| greenspan | -54.35 | greenspan | -51.38 | vioxx | -38.00 | risky | -125.76 |

| bush | -153.06 | bush | -143.02 | bush | -153.06 | bush | -253.95 |

| yesterday | -162.30 | yesterday | -151.71 | yesterday | -162.30 | yesterday | -268.29 |

As you can see, slight variations on keywording give different impressions of the same corpus!

A key strength of corpkit's approach to keywording is that you can generate new keyword lists without re-interrogating the corpus. We can use some Pandas syntax to do this more quickly.

>>> yrs = ['2011', '2012', '2013', '2014']

>>> keys = p.results.ix[yrs].sum().edit('keywords', p.results.drop(yrs),

... threshold=False)

>>> print keys.resultsOutput:

bank 1795.24

obama 722.36

romney 560.67

jpmorgan 527.57

rule 413.94

dimon 389.86

draghi 349.80

regulator 317.82

italy 282.00

crisis 243.43

putin 209.51

greece 208.80

snowden 208.35

mf 192.78

adoboli 161.30

... or track the keyness of a set of words over time:

>>> twords = ['terror', 'terrorism', 'terrorist']

>>> terr = p.edit(K, SELF, merge_entries={'terror': twords})

>>> print terr.results.terrorOutput:

1963 -2.51

1987 -3.67

1988 -16.09

1989 -6.24

1990 -16.24

... ...

Name: terror, dtype: float64

Naturally, we can use visualise() for our keywords too:

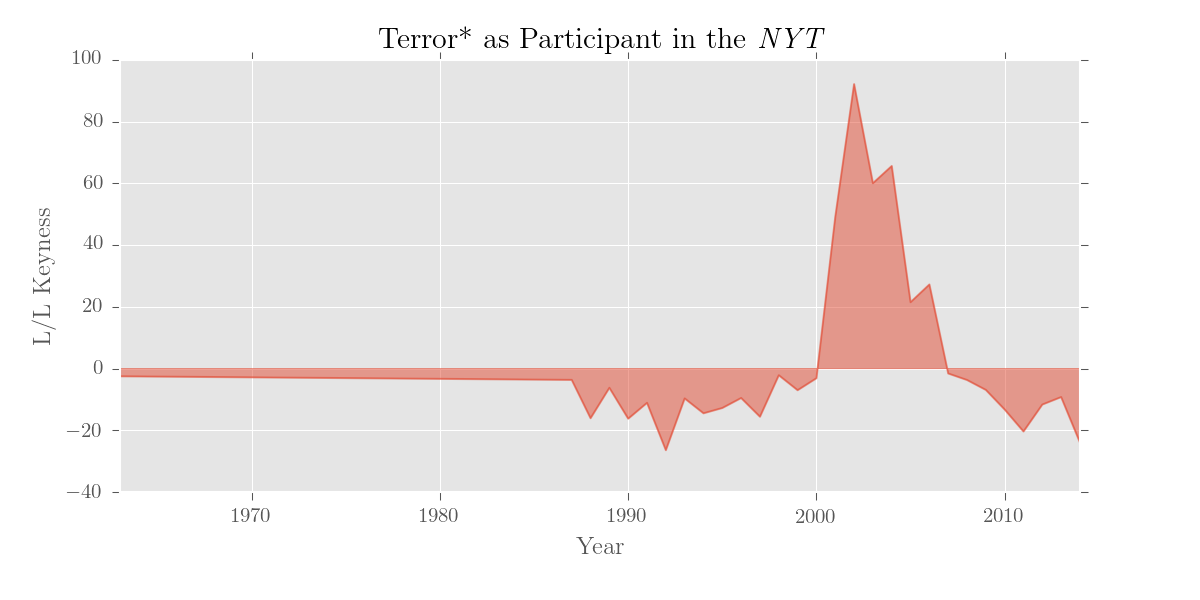

>>> pols.results.terror.visualise('Terror* as Participant in the \emph{NYT}',

... kind='area', stacked=False, y_label='L/L Keyness')

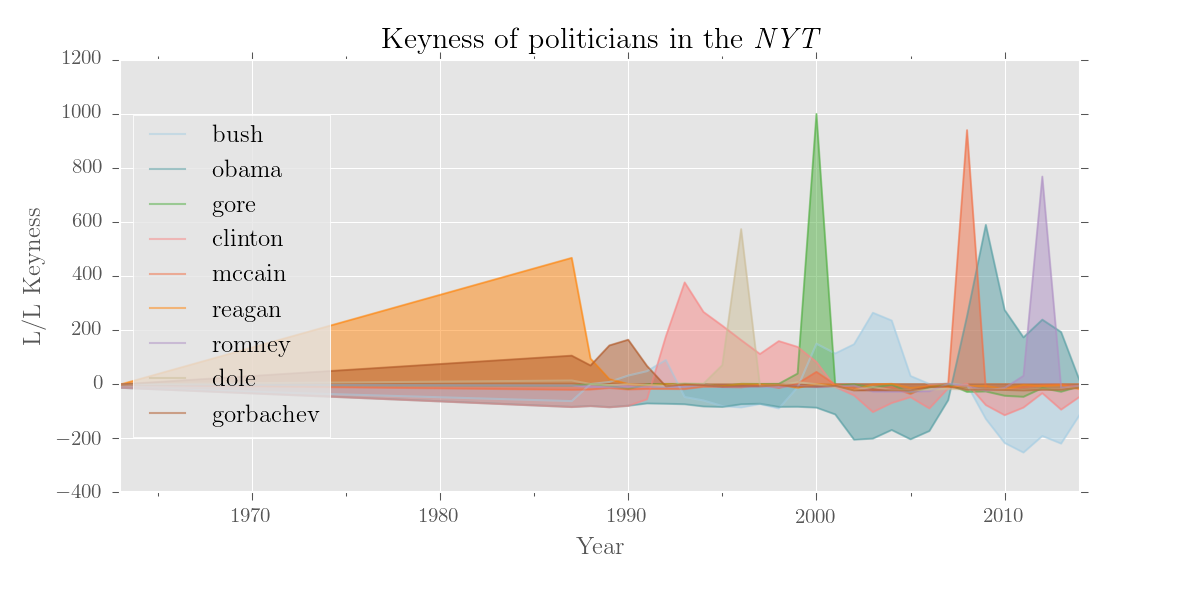

>>> politicians = ['bush', 'obama', 'gore', 'clinton', 'mccain',

... 'romney', 'dole', 'reagan', 'gorbachev']

>>> k.results[politicans].visualise('Keyness of politicians in the \emph{NYT}',

... num_to_plot='all', y_label='L/L Keyness', kind='area', legend_pos='center left')If you still want to use a standard reference corpus, you can do that (and a dictionary version of the BNC is included). For the reference corpus, edit() recognises dicts, DataFrames, Series, files containing dicts, or paths to plain text files or trees.

### arbitrary list of common/boring words

>>> from corpkit.dictionaries import stopwords

>>> print p.results.ix['2013'].edit(K, 'bnc.p', skip_entries=stopwords).results

>>> print p.results.ix['2013'].edit(K, 'bnc.p', calc_all=False).resultsOutput (not so useful):

#1 #2

bank 5568.25 bank 5568.25

person 5423.24 person 5423.24

company 3839.14 company 3839.14

way 3537.16 way 3537.16

state 2873.94 state 2873.94

... ...

three -691.25 ten -199.36

people -829.97 bit -205.97

going -877.83 sort -254.71

erm -2429.29 thought -255.72

yeah -3179.90 will -679.06

interrogate() can also do parallel-processing. You can generally improve the speed of an interrogation by setting the multiprocess argument:

### set num of parallel processes manually

>>> data = corpus.interrogate({T: r'/NN.?/ >># NP'}, multiprocess=3)

### set num of parallel processes automatically

>>> data = corpus.interrogate({T: r'/NN.?/ >># NP'}, multiprocess=True)Multiprocessing is particularly useful, however, when you are interested in multiple corpora, speaker IDs, or search queries. The sections below explain how.

To parallel-process multiple corpora, first, wrap them up as a Corpora() object. To do this, you can pass in:

- a list of paths

- a list of

Corpus()objects - A single path string that contains corpora

>>> from corpkit.corpus import Corpora

>>> corpora = Corpora('./data') # path containing corpora

>>> corpora

### <corpkit.corpus.Corpora instance: 6 items>

### interrogate by parallel processing, 4 at a time

>>> output = corpora.interrogate(T, r'/NN.?/ < /(?i)^h/', show=L, multiprocess=4)The output of a multiprocessed interrogation will generally be a dict with corpus/speaker/query names as keys. The main exception to this is if you use show=C, which will concatenate results from each query into a single Interrogation object, using corpus/speaker/query names as column names.

Passing in a list of speaker names will also trigger multiprocessing:

>>> from dictionary.wordlists import wordlists

>>> spkrs = ['MEYER', 'JAY']

>>> each_speaker = corpus.interrogate(W, wordlists.closedclass, just_speakers=spkrs)There is also just_speakers='each', which will be automatically expanded to include every speaker name found in the corpus.

You can also run a number of queries over the same corpus in parallel. There are two ways to do this.

### method one

>>> query = {'Noun phrases': r'NP', 'Verb phrases': r'VP'}

>>> phrases = corpus.interrogate(T, query, show=C)

### method two

>>> query = {'-ing words': {W: r'ing$'}, '-ed verbs': {P: r'^V', W: r'ed$'}}

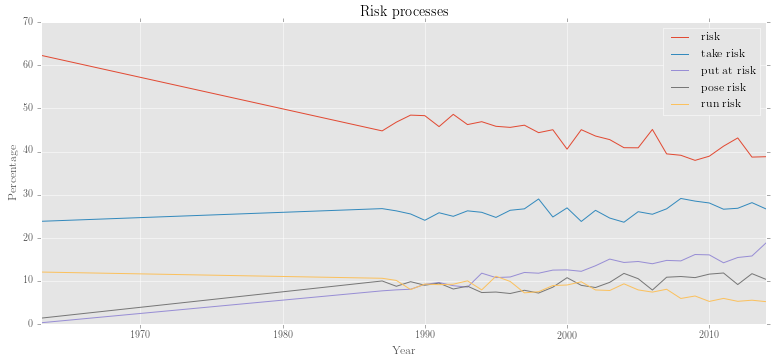

>>> patterns = corpus.interrogate(query, show=L)Let's try multiprocessing with multiple queries, showing count (i.e. returning a single results DataFrame). We can look at different risk processes (e.g. risk, take risk, run risk, pose risk, put at risk) using constituency parses:

>>> q = {'risk': r'VP <<# (/VB.?/ < /(?i).?\brisk.?\b/)',

... 'take risk': r'VP <<# (/VB.?/ < /(?i)\b(take|takes|taking|took|taken)+\b/) < (NP <<# /(?i).?\brisk.?\b/)',

... 'run risk': r'VP <<# (/VB.?/ < /(?i)\b(run|runs|running|ran)+\b/) < (NP <<# /(?i).?\brisk.?\b/)',

... 'put at risk': r'VP <<# /(?i)(put|puts|putting)\b/ << (PP <<# /(?i)at/ < (NP <<# /(?i).?\brisk.?/))',

... 'pose risk': r'VP <<# (/VB.?/ < /(?i)\b(pose|poses|posed|posing)+\b/) < (NP <<# /(?i).?\brisk.?\b/)'}

# show=C will collapse results from each search into single dataframe

>>> processes = corpus.interrogate(T, q, show=C)

>>> proc_rel = processes.edit('%', processes.totals)

>>> proc_rel.visualise('Risk processes')Output:

Next, let's find out what kinds of noun lemmas are subjects of any of these risk processes:

### a query to find heads of nps that are subjects of risk processes

>>> query = r'/^NN(S|)$/ !< /(?i).?\brisk.?/ >># (@NP $ (VP <+(VP) (VP ( <<# (/VB.?/ < /(?i).?\brisk.?/) ' \

... r'| <<# (/VB.?/ < /(?i)\b(take|taking|takes|taken|took|run|running|runs|ran|put|putting|puts)/) < ' \

... r'(NP <<# (/NN.?/ < /(?i).?\brisk.?/))))))'

>>> noun_riskers = c.interrogate(T, query, show=L)

>>> noun_riskers.quickview(10)Output:

0: person (n=195)

1: company (n=139)

2: bank (n=80)

3: investor (n=66)

4: government (n=63)

5: man (n=51)

6: leader (n=48)

7: woman (n=43)

8: official (n=40)

9: player (n=39)

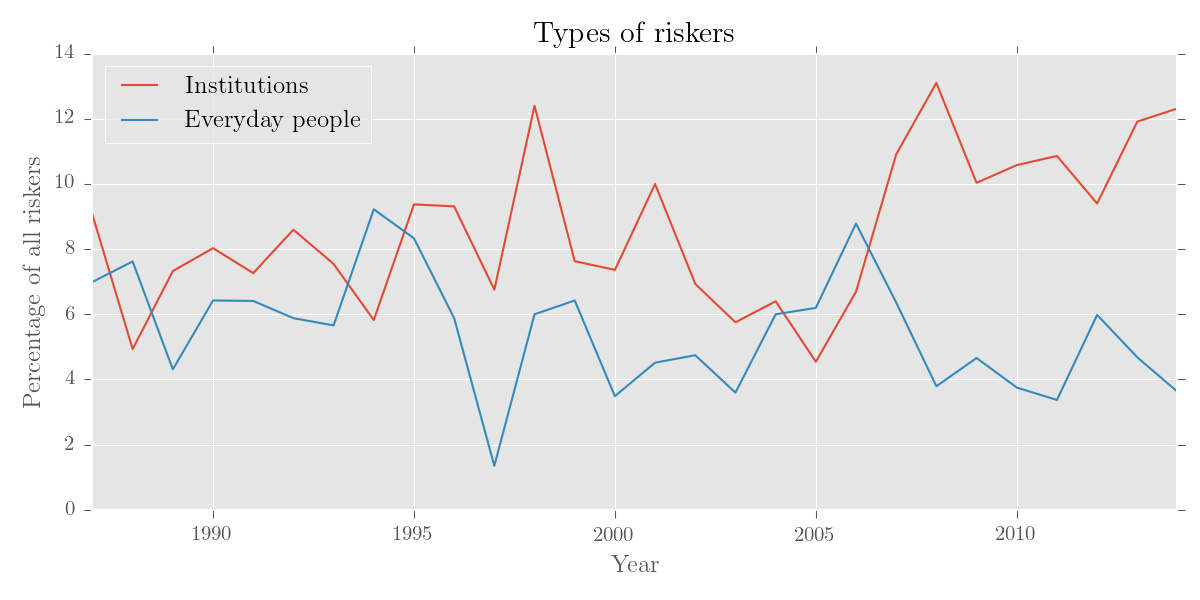

We can use edit() to make some thematic categories:

### get everyday people

>>> p = ['person', 'man', 'woman', 'child', 'consumer', 'baby', 'student', 'patient']

### get business, gov, institutions

>>> i = ['company', 'bank', 'investor', 'government', 'leader', 'president', 'officer',

... 'politician', 'institution', 'agency', 'candidate', 'firm']

>>> merges = {'Everyday people': p, Institutions: i}

>>> them_cat = them_cat.edit('%', noun_riskers.totals,

... merge_entries=merges,

... sort_by='total',

... skip_subcorpora=1963,

... just_entries=merges.keys())

### plot result

>>> them_cat.visualise('Types of riskers', y_label='Percentage of all riskers')Output:

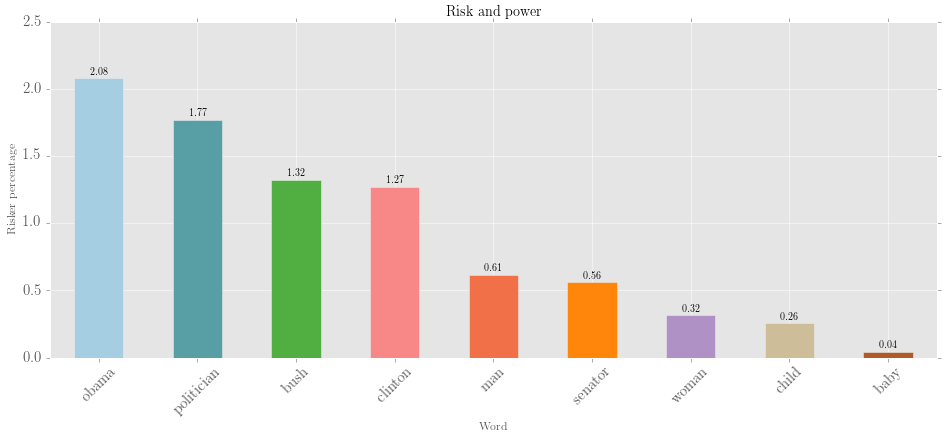

Let's also find out what percentage of the time some nouns appear as riskers:

### find any head of an np not containing risk

>>> query = r'/NN.?/ >># NP !< /(?i).?\brisk.?/'

>>> noun_lemmata = corpus.interrogate(T, query, show=L)

### get some key terms

>>> people = ['man', 'woman', 'child', 'baby', 'politician',

... 'senator', 'obama', 'clinton', 'bush']

>>> selected = noun_riskers.edit('%', noun_lemmata.results,

... just_entries=people, just_totals=True, threshold=0, sort_by='total')

### make a bar chart:

>>> selected.visualise('Risk and power', num_to_plot='all', kind='bar',

... x_label='Word', y_label='Risker percentage', fontsize=15)Output:

With a bit of creativity, you can do some pretty awesome data-viz, thanks to Pandas and Matplotlib. The following plots require only one interrogation:

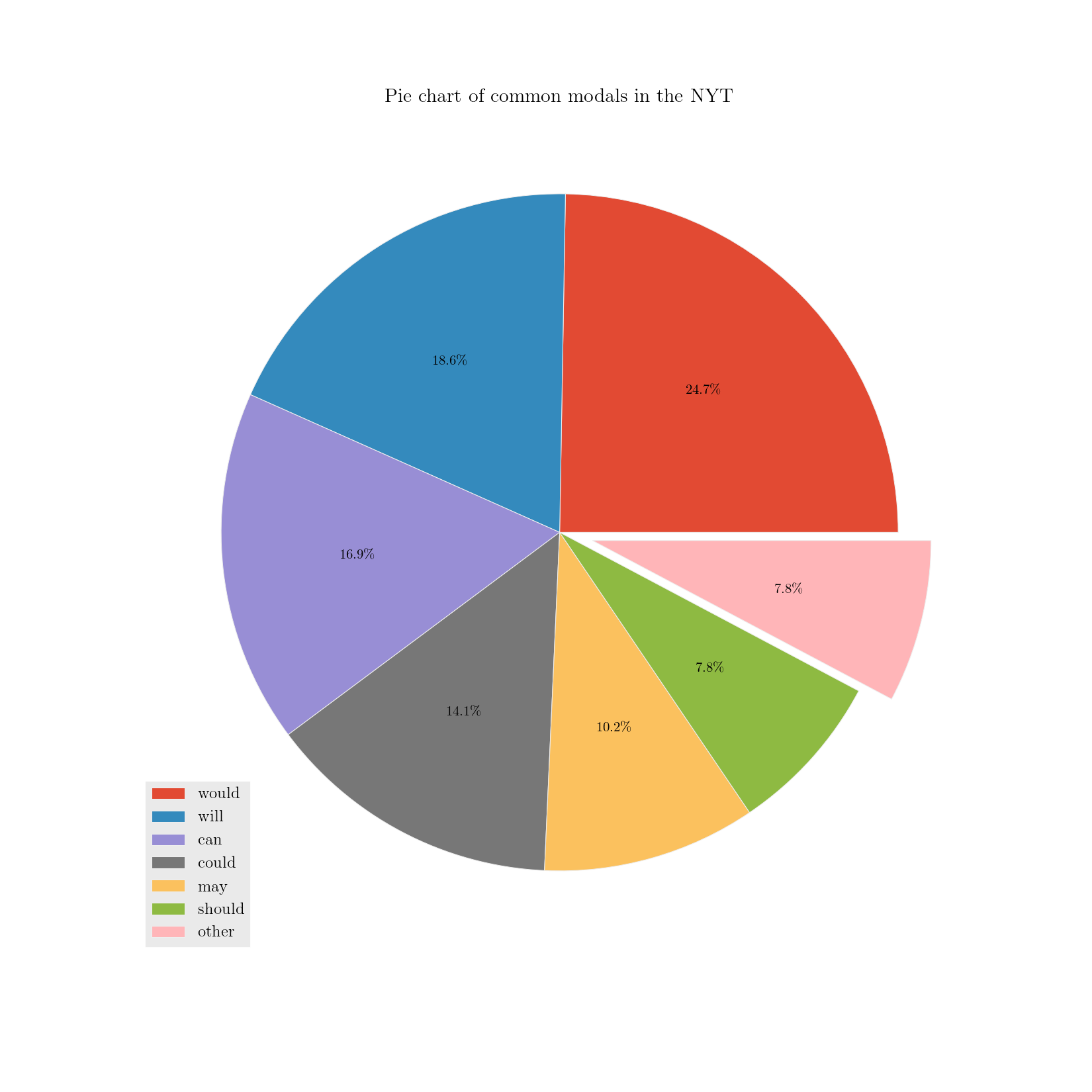

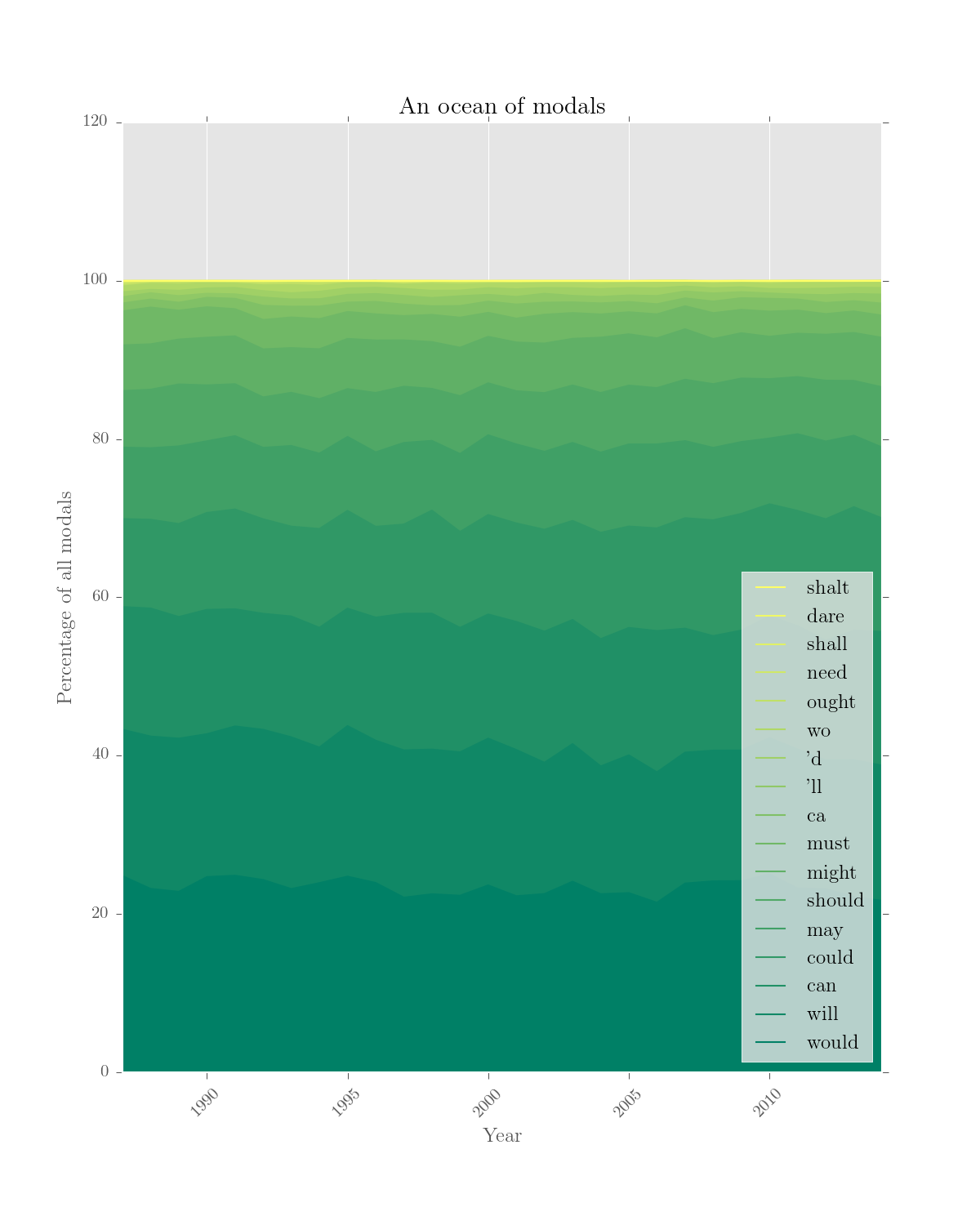

>>> modals = corpus.interrogate(T, 'MD < __', show=L)

### simple stuff: make relative frequencies for individual or total results

>>> rel_modals = modals.edit('%', modals.totals)

### trickier: make an 'others' result from low-total entries

>>> low_indices = range(7, modals.results.shape[1])

>>> each_md = modals.edit('%', modals.totals, merge_entries={'other': low_indices},

... sort_by='total', just_totals=True, keep_top=7)

### complex stuff: merge results

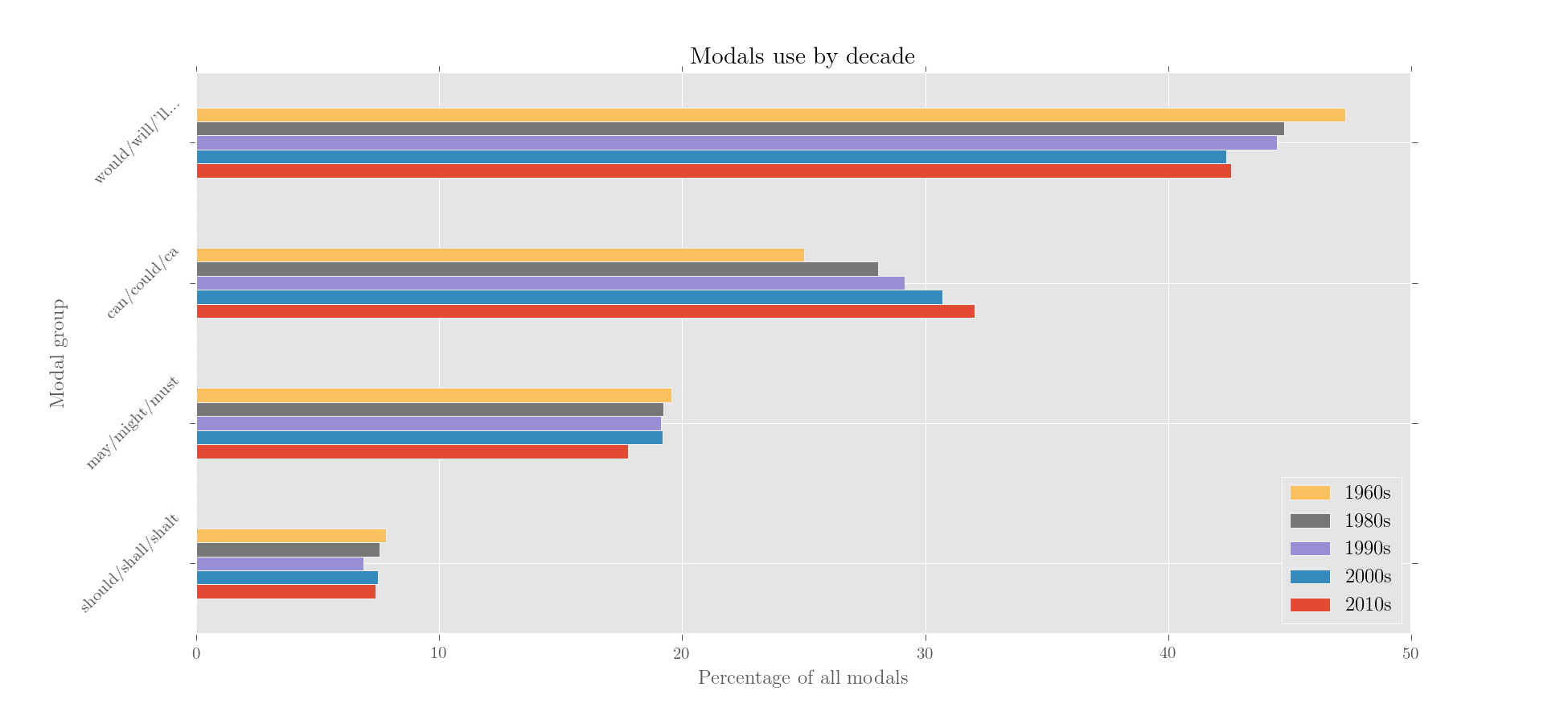

>>> entries_to_merge = [r'(^w|\'ll|\'d)', r'^c', r'^m', r'^sh']

>>> modals = modals.edit(merge_entries=entries_to_merge)

### complex stuff: merge subcorpora

>>> merges = {'1960s': r'^196',

... '1980s': r'^198',

... '1990s': r'^199',

... '2000s': r'^200',

... '2010s': r'^201'}

>>> modals = sayers.edit(merge_subcorpora=merges)

### make relative, sort, remove what we don't want

>>> modals = modals.edit('%', modals.totals, keep_stats=False,

... just_subcorpora=merges.keys(), sort_by='total', keep_top=4)

### show results

>>> print rel_modals.results, each_md.results, modals.resultsOutput:

would will can could ... need shall dare shalt

1963 22.326833 23.537323 17.955615 6.590451 ... 0.000000 0.537996 0.000000 0

1987 24.750614 18.505132 15.512505 11.117537 ... 0.072286 0.260228 0.014457 0

1988 23.138986 19.257117 16.182067 11.219364 ... 0.091338 0.060892 0.000000 0

... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ...

2012 23.097345 16.283186 15.132743 15.353982 ... 0.029499 0.029499 0.000000 0

2013 22.136269 17.286522 16.349301 15.620351 ... 0.029753 0.029753 0.000000 0

2014 21.618357 17.101449 16.908213 14.347826 ... 0.024155 0.000000 0.000000 0

[29 rows x 17 columns]

would 23.235853

will 17.484034

can 15.844070

could 13.243449

may 9.581255

should 7.292294

other 7.290155

Name: Combined total, dtype: float64

would/will/'ll... can/could/ca may/might/must should/shall/shalt

1960s 47.276395 25.016812 19.569603 7.800941

1980s 44.756285 28.050776 19.224476 7.566817

1990s 44.481957 29.142571 19.140310 6.892708

2000s 42.386571 30.710739 19.182867 7.485681

2010s 42.581666 32.045745 17.777845 7.397044

Now, some intense plotting:

### exploded pie chart

>>> each_md.visualise('Pie chart of common modals in the NYT', explode=['other'],

... num_to_plot='all', kind='pie', colours='Accent', figsize=(11,11))

### bar chart, transposing and reversing the data

>>> modals.results.iloc[::-1].T.iloc[::-1].visualise('Modals use by decade', kind='barh',

... x_label='Percentage of all modals', y_label='Modal group')

### stacked area chart

>>> rel_modals.results.drop('1963').visualise('An ocean of modals', kind='area',

... stacked=True, colours='summer', figsize =(8,10), num_to_plot='all',

... legend_pos='lower right', y_label='Percentage of all modals')Output:

Twitter: @interro_gator

McDonald, D. (2015). corpkit: a toolkit for corpus linguistics. Retrieved from https://www.github.com/interrogator/corpkit. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.28361