- Definition

- Process state

- Process Control Block (PCB)

- Process switching

- An operating system executes a variety of programs:

- Batch system – jobs

- Time-shared systems – user programs or tasks

- Textbook uses the terms job and process interchangeably

- Process

- a program in execution; process execution must progress in sequential fashion

- Program is passive entity stored on disk (executable file),

process is active

- Program becomes process when executable file is loaded into memory

- Execution of program started via GUI mouse clicks, command line entry of its name, etc.

- One program can be several processes

- Consider multiple users executing the same program

- Multiple parts

- The program code, also called text section

- Current activity including program counter, processor registers

- Data section containing global variables

- Stack containing temporary data

- Function parameters, return addresses, local variables

- Heap containing dynamically allocated memory

- The program code, also called text section

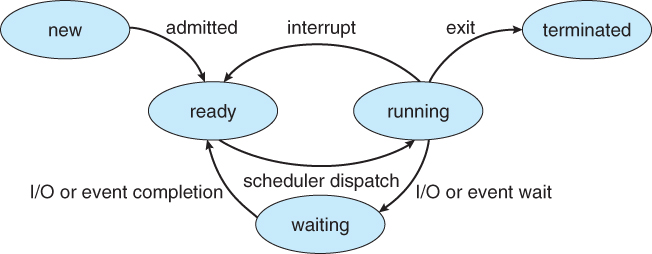

- As a process executes, it changes state

- new: The process is being created

- running: Instructions are being executed

- waiting: The process is waiting for some event to occur

- ready: The process is waiting to be assigned to a processor

- terminated: The process has finished execution

- Only one process can be run at a processor, but many can be “ready”, “waiting”

Information associated with each process (also called task control block)

- Process number – PID

- Process state – running, waiting, etc

- Program counter – location of instruction to next execute (bookmark)

- CPU registers – contents of all process-centric registers (Accumlators, stack pointer, …)

- CPU scheduling information – priorities, scheduling queue pointers

- Memory-management information – memory allocated to the process (base, limit, PT, …)

- Accounting information – CPU used, clock time elapsed since start, time limits

- I/O status information – I/O devices allocated to process, list of open files

Represented by the C structure task_struct

pid t_pid; /* process identifier */

long state; /* state of the process */

unsigned int time_slice /* scheduling information */

struct task_struct *parent; /* this process�s parent */

struct list_head children; /* this process�s children */

struct files_struct *files; /* list of open files */

struct mm_struct *mm; /* address space of this process */- PCB serves as the repository for any information that may vary from process to process.

- The state information must be saved when an interrupt occurs, to allow the process to be continued correctly afterward.

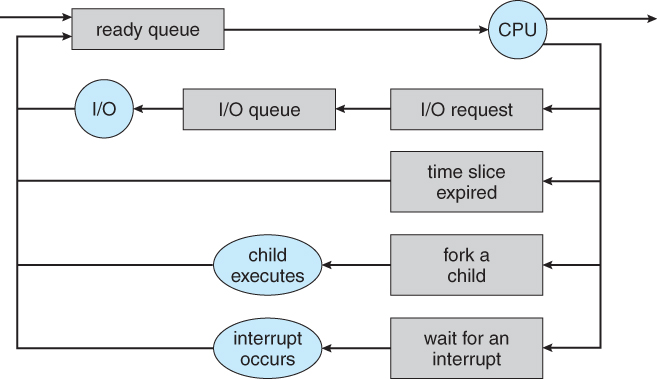

- Scheduling queues

- Schedulers

- Context switch

- If more than one processes exist, the rest must wait until the

CPU is freed by the running process. Scheduling is required in

- Multiprogramming to have some process running at all times

- Time-sharing to switch the CPU among processes by users.

- Process scheduler selects among available processes for next execution on CPU, maximize CPU use, quickly switch processes onto CPU for time sharing

- Maintains scheduling queues of processes

- Job queue – set of all processes in the system

- Ready queue – set of all processes residing in main memory, ready and waiting to execute

- Device queues – set of processes waiting for an I/O device

- Processes migrate among the various queues

- Linked list – A queue header contains pointers to the first and final PCBs in the list. Each PCB is extended to include a pointer field that points to the next PCB in the queue.

- Queuing diagram represents queues, resources, flows

- Short-term scheduler (or CPU scheduler) – selects which process in the

memory should be executed next and allocates CPU

- Sometimes the only scheduler in a system

- Short-term scheduler is invoked frequently (milliseconds) ⇒ (must be fast)

- Long-term scheduler (or job scheduler) – selects which processes should be

brought into the ready queue

- Long-term scheduler is invoked infrequently (seconds, minutes) ⇒ (may be slow)

- The long-term scheduler controls the degree of multiprogramming

- Processes can be described as either:

- I/O-bound process – spends more time doing I/O than computations, many short CPU bursts

- CPU-bound process – spends more time doing computations; few very long CPU bursts

- Long-term scheduler strives for good process mix

- Medium-term scheduler also called swapping swaps processes out of memory and later swaps them into the memory

- Reduces the degree of multiprogramming

- When CPU switches to another process, the system must save the state

of the old process and load the saved state for the new process via a

context switch

- Context of a process represented in the PCB

- Context-switch time is overhead – no useful work done while switching

- The more complex the OS/PCB => the longer the context switch

- Context-switch time is dependent on hardware support

- Some hardware provides multiple sets of registers per CPU => multiple contexts loaded at once

- Switching speed depends on memory speed, number of registers that must be copied, and special instructions (such as single instruction to load or store all registers)

- Typical speeds range from 1 to 1000 µs (very slow).

- Switching time may be bottleneck for complex OS.

- Process creation

- Process termination

-

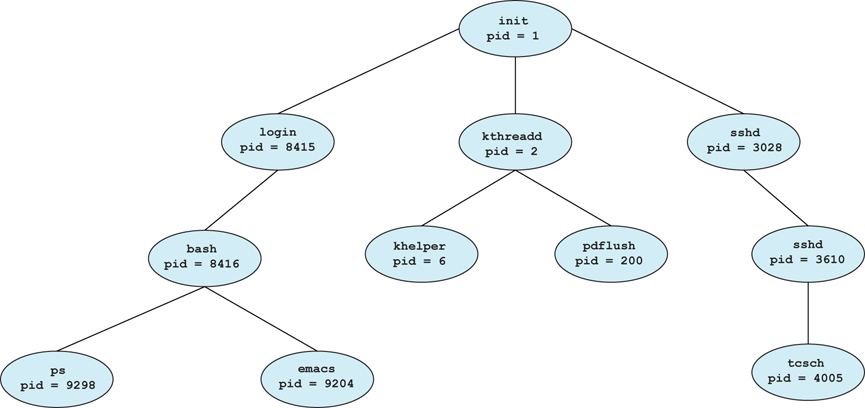

Parent process create children processes, which, in turn create other processes, forming a tree of processes

- Process identified and managed via a process identifier (pid)

-

Different potential resource sharing policies

- Parent and children share all resources

- Children share subset of parent’s resources

- Parent and child share no resources

-

Initialization data (e.g., input of file name)

- Passed along from parent to child process.

-

Two possibilities for execution

-

Address space

- Child duplicate of parent (same program and data)

- Child has a program loaded into it

-

UNIX examples

- fork system call creates new process

- exec system call used after a fork to replace the process’ memory space with a new program

int main()

{

pid_t pid;

/* fork another process */

pid = fork(); /* split happens here */

if (pid < 0) { /* error occurred */

fprintf(stderr, "Fork Failed");

exit(-1);

} else if (pid == 0) { /* child process */

execlp("/bin/ls", "ls", NULL);

} else { /* parent process */

/* parent will wait for the child to complete */

wait (NULL);

printf ("Child Complete");

exit(0);

}

}- Normal – Process executes last statement and asks the operating

system to delete it using

exit()syscall- Returns output status data from child to parent via

wait()syscall - Process’ resources are deallocated by operating system

- Returns output status data from child to parent via

- Abnormal – Parent may terminate execution of children processes using

abort()syscall- Child has exceeded allocated resources

- Task assigned to child is no longer required

- Some operating system do not allow child to continue if its parent

terminates

- All children terminated - cascading termination

- Some operating systems do not allow child to exists if its parent has

terminated. If a process terminates, then all its children must also be

terminated.

- cascading termination. All children, grandchildren, etc. are terminated.

- The termination is initiated by the operating system.

- The parent process may wait for termination of a child process by using the

wait()system call. The call returns status information and the pid of the terminated processpid = wait(&status); - If no parent waiting (did not invoke

wait()), the dead child process is a zombie- A process that finishes its execution and waiting for be reaped

- If parent terminated without invoking

wait, the live child process is an orphan- A process that loses its parent. In Linux, it will be adopted by

init.

- A process that loses its parent. In Linux, it will be adopted by

- IPC models

- Shared-memory model

- Bounded-buffer example

- Message passing systems

- Direct and indirect communication

- Synchronization

- Buffering

- Independent processes cannot affect or be affected by the execution of

another process.

- Such processes do not share any data.

- Cooperating processes can affect or be affected by the execution of

another process

- Such processes share data

- Interprocess communication (IPC) mechanisms allow such processes to exchange data and information

- Such processes need to be synchronized.

- Advantages of process cooperation

- Information sharing

- Computation speed-up

- Modularity

- Convenience

- Two IPC models

- Message passing – Useful for exchanging smaller amounts of data; Easier to implement through system calls but slower

- Shared memory – Allows maximum speed and convenience of communication; Faster accesses to shared memory

- An area of memory shared among the processes that wish to communicate

- The communication is under the control of the user processes

NOT the operating system

- Both advantages and disadvantages

- Major issues is to provide mechanism that will allow the user processes to synchronize their actions when they access shared memory.

- Synchronization is discussed in great details later.

- Shared-memory systems

- Communicating processes establish a region of shared memory. They can exchange information by reading and writing data in the shared areas.

- Paradigm for cooperating processes – producer process

produces information that is consumed by a consumer process

- e.g., a print program produces characters that are consumed by the printer driver.

- A buffer of items that can be filled by the producer and emptied by

the consumer. This buffer will reside in a region of memory that is

shared by both processes.

- Unbounded-buffer places no practical limit on the buffer size

- Bounded-buffer assumes a fixed buffer size

- Shared data

#define BUFFER_SIZE 10

typedef struct {

// . . .

} item;

item buffer[BUFFER_SIZE];

int in = 0; // next free position

int out = 0; // first full position- Solution is correct, but can only use

BUFFER_SIZE-1elements - The shared buffer is implemented as a 8circular array with two logical pointers: in and out.

- The producer process has a local variable item in which the new item to be produced is stored:

while (true) {

/* Produce an item */

while (((in + 1) % BUFFER SIZE count) == out)

; /* do nothing -- no free buffers */

buffer[in] = item;

in = (in + 1) % BUFFER SIZE;

}- The consumer process has a local variable item in which the item to be consumed is stored:

while (true) {

while (in == out)

; // do nothing -- nothing to consume

// remove an item from the buffer

item = buffer[out];

out = (out + 1) % BUFFER SIZE;

return item;

}- Mechanism for processes to communicate and to synchronize their actions

- Message system – processes communicate with each other without resorting to shared variables

- Useful in distributed systems via network

- IPC facility provides two operations:

- Send(message) – message size fixed or variable

- Receive(message)

- If P and Q wish to communicate, they need to:

- establish a communication link between them

- exchange messages via send/receive

- Implementation issues of communication link

- Physical (e.g., shared memory, hardware bus, network)

- Logical (Direct vs. indirect, sync vs. async, auto vs. explicit buffering)

Implementation Questions

- How are links established?

- Can a link be associated with more than two processes?

- How many links can there be between every pair of communicating processes?

- What is the capacity of a link? (e.g., buffer size, etc.)

- Is the size of a message that the link can accommodate fixed or variable?

- Is a link unidirectional or bi-directional?

- Can data flow only in one direction or both directions?

- Unidirectional: message can be only be sent or received but not both

- Processes must name each other explicitly:

- send(P, message) – send a message to process P

- receive(Q, message) – receive a message from process Q

- Properties of communication link

- Links are established automatically

- A link is associated with exactly one pair of communicating processes

- Between each pair there exists exactly one link

- The link may be unidirectional, but is usually bi-directional

- Asymmetry in addressing – Only sender names the recipient; the recipient

is not required to name the sender

- send(P, message) – send a message to process P

- receive(id, message) – receive from any process, id set to the sender

- Disadvantage – A limited modularity of the resulting process definitions

- Changing process ID requires to update all references (like change phone numbers)

- Messages are directed and received from mailboxes (or ports)

- Each mailbox has a unique ID

- Processes can communicate only if they share a mailbox

- Properties of communication link

- Link established only if processes share a common mailbox

- A link may be associated with many processes

- Each pair of processes may share several mailboxes if desired

- Link may be unidirectional or bi-directional

- Assuming a Mailbox sharing

- P1, P2, and P3 share mailbox A

- P1, sends; P2 and P3 receive

- Who gets the message?

- Solutions depend on the mechanisms we choose

- Allow a link to be associated with at most two processes

- Allow only one process at a time to execute a receive operation

- Allow the system to select arbitrarily the receiver. Sender is notified who the receiver was.

- Mailbox ownership

- A mailbox may be owned by a particular process or OS

- Owner process can only receive message through the mailbox

- User process can only send message through the mailbox

- Mailbox disappears when the owner process terminates

- A mailbox can be owned by OS and independent from any process

- create a new mailbox

- send and receive messages through mailbox

- destroy a mailbox

- A mailbox may be owned by a particular process or OS

- Primitives are defined as:

- send(A, message) – send a message to mailbox A

- receive(A, message) – receive a message from mailbox A

- Message passing may be either blocking or non-blocking

- Blocking is considered synchronous

- Blocking send -- the sender is blocked until the message is received

- Blocking receive -- the receiver is blocked until a message is available

- Non-blocking is considered asynchronous

- Non-blocking send -- the sender sends the message and continue

- Non-blocking receive -- the receiver receives:

- A valid message, or null message

- Different combinations possible

- If both send and receive are blocking, we have a rendezvous

- Sender sends a message and waits until it is delivered

- Receiver blocks until a message is available

Synchronous and asynchronous I/O is a basic concept in OS

- Producer-consumer becomes trivial

message next_produced;

while (true) {

/* produce an item in next produced */

send(next_produced);

}

message next_consumed;

while (true) {

receive(next_consumed);

/* consume the item in next consumed */

}- Messages exchanged by processes reside in a temporary queue during communication.

- Queue of messages attached to the link; implemented in one of three ways

- Zero capacity – 0 messages

- Sender must wait for receiver (rendezvous)

- Bounded capacity – finite length of n messages

- Sender must wait if link full

- Unbounded capacity – infinite length

- Sender never waits

- POSIX Shared Memory

- Process first creates shared memory segment

shm_fd = shm_open(name, O CREAT | O RDWR, 0666);

- Also used to open an existing segment to share it

- Set the size of the object

ftruncate(shm_fd, 4096);

- Mmap the shared memory object

mmap(0, 4096, PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, shm_fd, 0);

- Now the process could write to the shared memory

sprintf(ptr, "Writing to shared memory");

- Process first creates shared memory segment

- Sockets

- Remote procedure calls (RPC)

- Remote method invocation (Java)

- A socket is defined as an endpoint for communication.

- A pair of processes communicating over a network employs a pair of sockets – one for each process

- Each socket is made up of an IP address concatenated with a port

number

- The socket 161.25.19.8:1625 refers to port 1625 on host 161.25.19.8

- 127.0.0.1 (loopback) refers to the localhost (the machine itself)

- Port numbers below 1024 are considered for standard services

- E.g., telnet (23), ftp (21), and http (80).

- When a client process initiates a request for a connection, it is

assigned a port by the host computer (with port number > 1024).

- All connections must be unique with each process having a different port number

Socket Communication

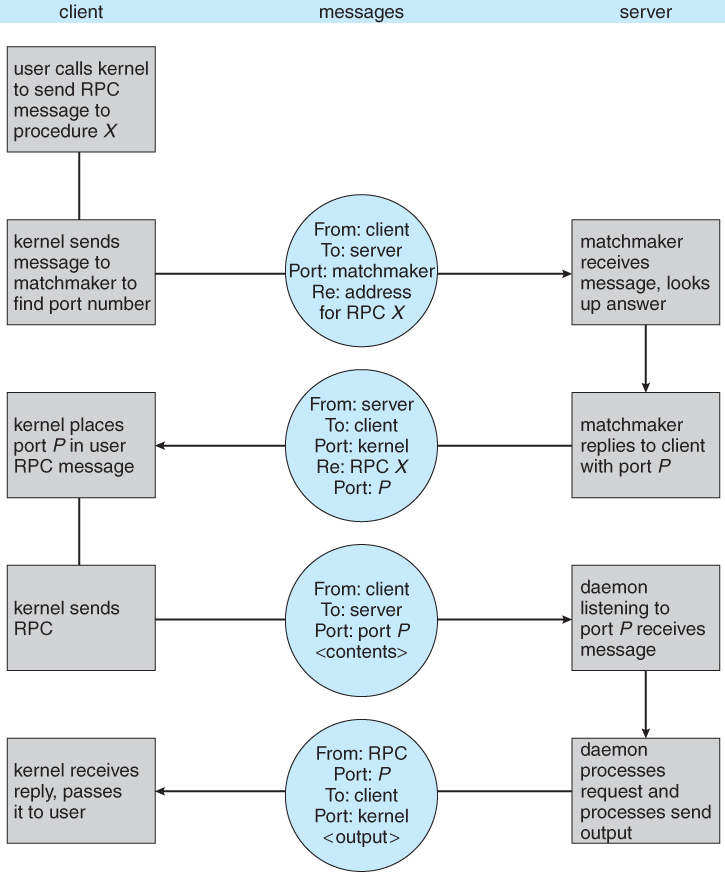

- Remote procedure call (RPC) abstracts procedure calls

between processes on networked systems

- Again uses ports for service differentiation

- Stubs – client-side proxy for the actual procedure on the server

- The client-side stub locates the server and marshalls the parameters

- The server-side stub receives this message, unpacks the marshalled parameters, and performs the procedure on the server

- On Windows, stub code compile from specification written in Microsoft Interface Definition Language (MIDL)

- Data representation handled via External Data Representation (XDL)

format to cope with different architectures

- Big-endian (most significant byte first, IBM z/Architecture) and little-endian (least significant byte first, Intel x86)

- Remote communication has more failure scenarios than local

- Messages can be delivered exactly once rather than at most once

- OS typically provides a rendezvous (or matchmaker) service to connect client and server

- Remote Method Invocation (RMI) is a Java mechanism similar to RPCs

- RMI allows a Java program on one machine to invoke a method on a remote object

- Acts as a conduit allowing two processes to communicate

- Four issues need to be considered in implementation of pipes

- Is communication unidirectional (like radio) or bidirectional?

- In the case of two-way communication, is it half (like walkie-talkie) or full-duplex (like phone)?

- Must there exist a relationship (i.e., parent-child) between the communicating processes?

- Can the pipes be used over a network?

- Ordinary pipes – cannot be accessed from outside the process that

created it.

- Typically, a parent process creates a pipe and uses it to communicate with a child process that it created.

- Named pipes* – can be accessed without a parent-child relationship.

- Ordinary Pipes allow communication in standard producer-consumer style

- Producer writes to one end (the write-end of the pipe)

- Consumer reads from the other end (the read-end of the pipe)

- Ordinary pipes are therefore unidirectional

- Require parent-child relationship between communicating processes

- Windows calls these anonymous pipes

- See Unix and Windows code samples in textbook

- Example

- Named Pipes (or FIFOs in UNIX) are more powerful than ordinary

pipes

- Communication is bidirectional

- No parent-child relationship is necessary between the communicating processes

- Pipes continue to exist after processes have finished

- Several processes can use the named pipe for communication

- Provided on both UNIX and Windows systems

- On UNIX, FIFOs can be created with mkfifo(), and operated with open(), read(), write(), close() syscalls.

- FIFOs allow bidirectional but only half-duplex transmission.

- Windows provides a richer mechanism (full-duplex, networkable)

- A process (or task) is a program in execution.

- It changes state as it executes.

- Each process is represented by its own PCB.

- Processes can be created and terminated dynamically.

- Process scheduling:

- Scheduling queues (ready and I/O queues)

- Long-term (job) and short term (CPU) schedulers.

- Processes can execute concurrently

- Information sharing, computation speed up, modularity, and convenience.

- Cooperating processes need to communicate each other using two IPC

models:

- Shared memory – by sharing some variables

- Message systems – by exchanging messages

- Communication:

- Using sockets – one at each end of the communication channel.

- RPC – a process calls a procedure on a remote application.

- RMI – Java version of RPC invoking a method on a remote object.

- Pipes